A few years ago, I sipping tea at my friend’s place after an intense week at work.

After chatting for a while, we naturally fell into a comfortable silence. Then, a few moments later I blurted out:

“My brain just needs some Screen Saver Mode!”

We both burst out laughing.

You see, for me—‘screen saver mode’ meant ‘switching my brain off’ for a bit—I was awake and aware, just not DOING anything.

Normally I’d sit and stare out of a window until people started asking questions.

Little did I know…

When I was busy staring off into space—my brain was FAR from ‘switched-off’.

And this ‘zoning out’ was actually a very healthy, normal reaction to periods of intense mental activity. For me it’s usually studying, writing, meetings, or admin work.

So… if you’ve ever felt guilty about resting, staring into space, or giving yourself down time—this article is for you.

Surprise!—

Your brain has a WHOLE NETWORK for screen saver mode.

And it’s not passive at all!

In 2001, neurologist Marcus E. Raichle (et. al.,) published a paper1 indicating our brain is REALLY active even when we are resting.

He called these interconnected regions the Default Mode Network.

Let’s call it DMN for short.

Basically—these regions of the brain light up when you’re in a ‘wakeful resting state’.

Think daydreaming, zoning out, autopilot, or as I put it—screen saver mode!

And when you’re paying focused attention to something—like reading, problem solving, talking, working etc.—these same regions are relatively quiet and not very active.

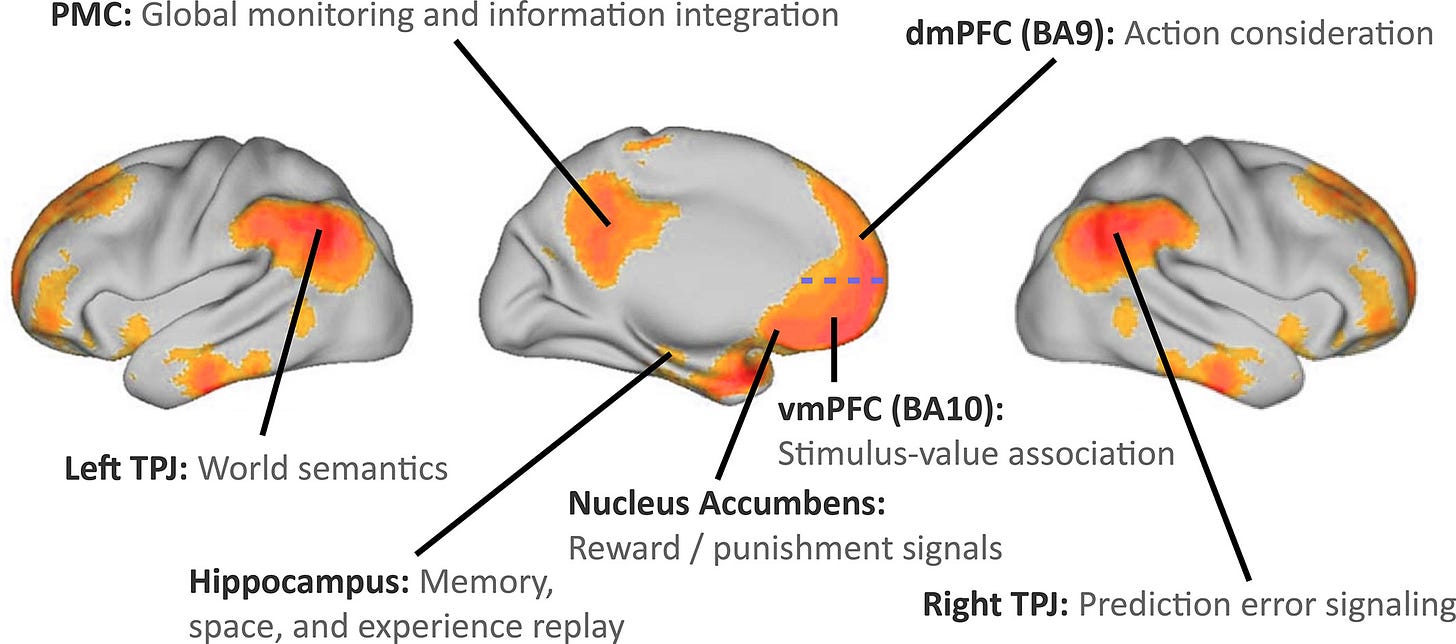

Here they are below:

Here’s what these regions do:

The Future Evaluator: helps you evaluate how great or terrible your future actions and plans will be. (Dorsal medial prefrontal cortex)2

The Reward Predictor: helps you to create expectations about future rewards in relationship to the how the world acts around you. (Ventral medial prefrontal cortex)3

The Self-Reflector: helps you recall your autobiographical memories and decides which emotions to pair with the memories. (Posterior cingulate cortex)4

The Motivation Translator: helps you translate motivation into action by deciding whether said action will lead to pain or pleasure. It's a key node in your reward system. (Nucleus accumbens)5

The Memory Maker: helps you encode, sort, categorise, store, and recall memories and the emotions that go with them. (Hippocampus)6

The Navigation Wizard: helps you create a physical map of your world and how it relates to your actual body. It’s also uses memory to help you navigate yourself through space and time. (Retrosplenial cortex)7

The Language Mapper: helps you understand how words and language are grouped together and how they relate to your body. (Inferior parietal lobe)8

Phew!

That’s a lot of activity!

And that’s not an exhaustive list! Just some of the major active, connected areas.

So, what does all this mean?

It means even when you’re doing ‘nothing’—your brain is still in full action.

And all this action is involved in exploring how YOU relate to your environment.

When you’re in your DMN, you’ll loosely ask yourself questions like:

how is everything going?

who am I today?

do I like the way things are?

what should I do tomorrow/next week/next year?

what’s important to me now?

what would I like for the future?

what’s going to happen next week?

where should I go tomorrow?

Then your mind will start giving you gentle hallucinations—scenarios played out on the movie screen of your mind.

You will spontaneously dream up potential answers to the questions that drift across your consciousness. For example:

you’ll think about cooking that delicious dinner you’ve had 3 nights in a row and still not sick of

you’ll picture yourself going for a walk at sunset and feeding the birds

you’ll picture yourself finally graduating and getting your degree, walking across the stage and waving at the people you love

you’ll remember the last time you read an incredible novel and decide to re-read it (ahem Lord of the Rings ahem)

you’ll think about someone you love and decide to call them later

you’ll remember this article and catch yourself next time you’re in screen saver mode

These thoughts are not intentional or focused.

They slip in and out of your attention.

They morph from one to the next effortlessly.

And they are all to do with YOU.

And they are crucial for your wellbeing.9

There has to be a reason for this, right?

Well—the DMN might give us an evolutionary advantage10 because animals that can imagine a range of different experiences and better anticipate the future might last a little longer.

In fact, all mammals have a DMN—including chimps, mice, ferrets, mouse lemurs, marmosets, and humans (cute pics below).

Other studies also suggest better functionality and connectivity in the DMN is linked with higher wellbeing.11

So what if this diffuse form of brain activity could help us live happier and healthier lives?

In fact, neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's, Alzheimer's show neural degeneration in areas similar to the DMN.1213 These symptoms include things like:

autobiographical confusion: trouble remembering recent things about one's self and who you are.

spatial confusion: not knowing where you are even in familiar locations.

physical difficulties: having trouble controlling your body in relation to your environment.

frustration and forgetfulness: not knowing who people are or what you’re supposed to do when and where.

Without your DMN—you might literally forget who you are!

So if you’re feeling guilty about ‘zoning out’, being on autopilot, or screen saver mode—don’t be!

Your brain is still active and working to improve your life and circumstances even when you’re not doing anything.

Take a moment to rest when you’re feeling stressed, overwhelmed, or overworked. Your DMN will take over and help you solve problems without the mental gymnastics.

However—

A word of warning

You don’t want to spend TOO much time in your DMN.

An over-active DMN has been linked with higher rates of depression, bi-polar, and other mood disorders.14

This is because your DMN is concerned with how YOU—Tim, Jane, Karen, [your name here]—relate to your environment. And if it’s active too often for too long—you might start ‘over-thinking’. This could look like:

over-connecting yourself to external events—a.k.a. blaming yourself for everything

ruminating, worrying, or stressing about yourself and/or others

replaying embarrassing, hurtful, or emotionally difficult memories over and over

Please note: this is not clinical advice but if the above sound a little too familiar—you could try some activities to take you OUT of your DMN. Like:

drawing a picture, doing a puzzle, crossword, or word search

re-organising your desk, office, bedroom, or kitchen

going for a walk or moving your body

Or anything else that needs your focused attention—even if it’s as simple as drawing circles on paper, or writing numbers down on the page.

Almost any activity that requires focus will take you out of your DMN—it’s all about finding what works for you.

The Goldilocks amount of DMN

So—as with most things in life—it seems we need a healthy balance of DMN activation and de-activation. Say:

enough so we have down-time, reflection, and breaks after strenuous tasks

not so much that we get lost in ruminating, worrying, or dissociative thoughts

So…

What might be the perfect amount of DMN for you?

I’ll leave you to ponder those thoughts… and maybe they’ll even enter your DMN later!

Enjoy that screen saver mode!

For the nerds 🤓

Watch a full 1.5hr lecture on the DMN from Stanford Psychedelic Science Group (includes Q&A with neurologist M.E. Raichle who coined the phrase Default Mode Network).

Cool videos: DMN in 2 minutes, lack of DMN activation and the psychedelic experience, DMN and depression.

This 2019 study explores a more comprehensive neuroanatomical model of the DMN including subcortical structures: basal forebrain, cholinergic nuclei, anterior, and mediodorsal thalamic nuclei. Neuroscience changes at a rather alarming pace and because the brain is INSANELY interconnected (think at least 60 TRILLION connections), so the literature is bound to constantly shift.

Go deeper: The DMN can be broken into two subsets: present self-reflection (anterior DMN) and future self-reflection (posterior DMN).

Extend your knowledge: How your social skills, understanding, and awareness overlap with DMN.

Links to other papers I’ve referenced:

Ruppert, M. C., Greuel, A., Freigang, J., Tahmasian, M., Maier, F., Hammes, J., van Eimeren, T., Timmermann, L., Tittgemeyer, M., Drzezga, A., & Eggers, C. (2021). The default mode network and cognition in Parkinson's disease: A multimodal resting‐state network approach. Human Brain Mapping, 42(8), 2623-2641. doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25393

One of my favorite things to do for my brain is ZONE OUT!